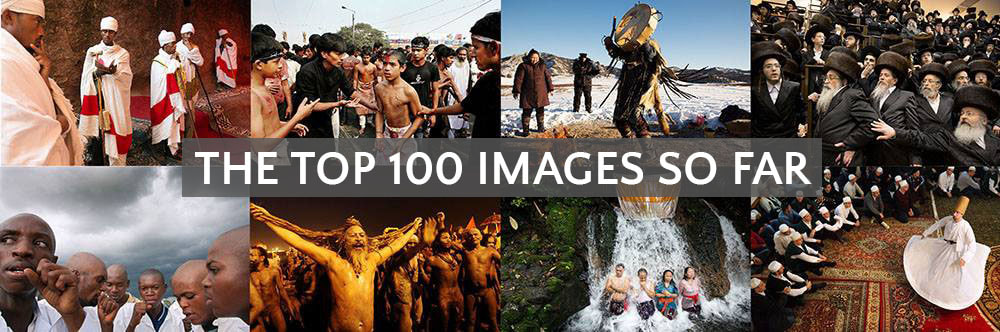

FACES OF FAITH PROJECT

Southern Asia

Southeastern Asia

Western Asia

Central and Eastern Asia

Eastern Europe

Southern Europe

Africa

FACES OF FAITH

When I was growing up in Communist Czechoslovakia, my teachers told me that there is no God and that religion is the opium of the people. Many years later I embarked on a personal journey: to observe people who believe in gods, and maybe, at the end of the journey, to find God.

When I was little, opulent baroque churches and severe gothic cathedrals alike were empty, and my grandparents didn’t attend church even on the major holidays.

In the early 1990s, as a photojournalist I travelled to wars in the former Yugoslavia and the Caucasus – Nagorno Karabakh, Abkhazia, Chechnya, and Kosovo, where mass murder was being committed in the name of God and nation. I couldn’t understand how faith could be so important that it would make you go and kill your neighbour.

In 2001 I travelled to Allahabad, India for the Maha Kumbh Mela mass Hindu pilgrimage. In the chilly January weather, 40 million pilgrims arrived to wash away their sins in holy waters. I wondered at the force that could motivate millions of people to embark on this exhausting journey, for some thousand of kilometres long. In morning mists and by evening fires, I saw hundreds of naked sadhus covered in nothing but ashes. They had renounced all possessions, abandoned their families, and set out on a spiritual journey. I met a holy man who had raised his arm in the year of my birth, and as far as I know is still holding it aloft to this day, forty-five years later. I left, quite fascinated and resolved to explore manifestations of faith wherever and whenever possible.

In Iraq I walked in a holy procession of men in white robes who slashed their heads with long knives. Blood squirted everywhere and I tried to refrain from condemning them. After Saddam Hussein’s regime fell, the oppressed Shias could finally freely mourn the death of Imam Husayn – the grandson of the Prophet himself, who fell in the Battle of Karbala.

In the Congo I participated in Pentecostal services during which demons were exorcised from the faithful. These endless rituals are accompanied by screaming and shouting, wild drumming and singing, and are very impressive. Regardless of whether possession is feigned or not, I think that the spread of the Pentecostal movement has a positive effect on Congolese society – in structures more reminiscent of shacks than churches, pastors preach that one should not drink alcohol, steal, or rape and beat your women. In a country that for many years had no rules, the faithful are beginning to listen. And their numbers are increasing.

I didn’t start believing in spirits or demons, but when a female Mongolian shaman placed her hand near mine, I felt heat, as if it were burning. From spirits that entered a medium during the Lên đồng ritual belonging to the ancient Vietnamese mother goddess religion, I received money, sweets, and even cigarettes. On the Thai island of Phuket I observed local Chinese entering into a trance so that the gods could enter their bodies. They then have their faces pierced by one or even several large swords, set out on a long procession through the town, and not even a drop of blood would seep from their wounds.

I became an intruder in quiet monastery worlds nestled in Romanian and Ethiopian hills or among the peaks of the Himalayans. I had audiences with living goddesses in the Kathmandu Valley, one of which befriended my wife and me.

During wild drinking sprees in small Polish towns with Hasidic Jews, I commemorated the deaths of their miraculous rabbis, and for a couple of days had the feeling that the world of Eastern European Jews that had disappeared forever in the ovens of Auschwitz had once again come to life.

I was a guest of Sufi brotherhoods in the Balkans. When during the Zikr ritual, dozens of men sway rhythmically in a circle and shout out holy verses, the energy that emanates from them sends shivers down my back, just like when Tibetan monks repeat their mantras.

Many times, I was invited to a feast. I ate sacrificed sheep with Muslims and Hindus. I stuffed myself to bursting with the salmon and caviar of mountain Jews in Azerbaijan, accompanied by much vodka. On the island of Sulawesi I feasted on freshly sacrificed water buffalo that were supposed to accompany the souls of dead Toraja to Puya (the land of souls). And everywhere people were kind, and like me were unable to understand how someone could kill in the name of faith.

No, I didn’t start believing in God, and perhaps on occasion only felt his uncertain presence. I joined no religion, but to be on the safe side, lit a candle everywhere I could – for my Dad and my other ancestors, wherever they may be.

When I was little, opulent baroque churches and severe gothic cathedrals alike were empty, and my grandparents didn’t attend church even on the major holidays.

In the early 1990s, as a photojournalist I travelled to wars in the former Yugoslavia and the Caucasus – Nagorno Karabakh, Abkhazia, Chechnya, and Kosovo, where mass murder was being committed in the name of God and nation. I couldn’t understand how faith could be so important that it would make you go and kill your neighbour.

In 2001 I travelled to Allahabad, India for the Maha Kumbh Mela mass Hindu pilgrimage. In the chilly January weather, 40 million pilgrims arrived to wash away their sins in holy waters. I wondered at the force that could motivate millions of people to embark on this exhausting journey, for some thousand of kilometres long. In morning mists and by evening fires, I saw hundreds of naked sadhus covered in nothing but ashes. They had renounced all possessions, abandoned their families, and set out on a spiritual journey. I met a holy man who had raised his arm in the year of my birth, and as far as I know is still holding it aloft to this day, forty-five years later. I left, quite fascinated and resolved to explore manifestations of faith wherever and whenever possible.

In Iraq I walked in a holy procession of men in white robes who slashed their heads with long knives. Blood squirted everywhere and I tried to refrain from condemning them. After Saddam Hussein’s regime fell, the oppressed Shias could finally freely mourn the death of Imam Husayn – the grandson of the Prophet himself, who fell in the Battle of Karbala.

In the Congo I participated in Pentecostal services during which demons were exorcised from the faithful. These endless rituals are accompanied by screaming and shouting, wild drumming and singing, and are very impressive. Regardless of whether possession is feigned or not, I think that the spread of the Pentecostal movement has a positive effect on Congolese society – in structures more reminiscent of shacks than churches, pastors preach that one should not drink alcohol, steal, or rape and beat your women. In a country that for many years had no rules, the faithful are beginning to listen. And their numbers are increasing.

I didn’t start believing in spirits or demons, but when a female Mongolian shaman placed her hand near mine, I felt heat, as if it were burning. From spirits that entered a medium during the Lên đồng ritual belonging to the ancient Vietnamese mother goddess religion, I received money, sweets, and even cigarettes. On the Thai island of Phuket I observed local Chinese entering into a trance so that the gods could enter their bodies. They then have their faces pierced by one or even several large swords, set out on a long procession through the town, and not even a drop of blood would seep from their wounds.

I became an intruder in quiet monastery worlds nestled in Romanian and Ethiopian hills or among the peaks of the Himalayans. I had audiences with living goddesses in the Kathmandu Valley, one of which befriended my wife and me.

During wild drinking sprees in small Polish towns with Hasidic Jews, I commemorated the deaths of their miraculous rabbis, and for a couple of days had the feeling that the world of Eastern European Jews that had disappeared forever in the ovens of Auschwitz had once again come to life.

I was a guest of Sufi brotherhoods in the Balkans. When during the Zikr ritual, dozens of men sway rhythmically in a circle and shout out holy verses, the energy that emanates from them sends shivers down my back, just like when Tibetan monks repeat their mantras.

Many times, I was invited to a feast. I ate sacrificed sheep with Muslims and Hindus. I stuffed myself to bursting with the salmon and caviar of mountain Jews in Azerbaijan, accompanied by much vodka. On the island of Sulawesi I feasted on freshly sacrificed water buffalo that were supposed to accompany the souls of dead Toraja to Puya (the land of souls). And everywhere people were kind, and like me were unable to understand how someone could kill in the name of faith.

No, I didn’t start believing in God, and perhaps on occasion only felt his uncertain presence. I joined no religion, but to be on the safe side, lit a candle everywhere I could – for my Dad and my other ancestors, wherever they may be.

SO FAR THE PROJECT INCLUDES THESE TOPICS :

|

- Shamanism in Mongolia

- Easter celebrations in Egypt, Germany, Georgia, Spain, Italy (Sardinia, Sicily) - Shia Islam - Ashura mourning in Iraq and India - Pentecostal churches in Congo - Christmas pigrimage to Lalibela, Ethiopia - Dao Mau cult (The Worship of Mother Goddess) in Vietnam - numerous Hindu festivals and pilgrimages photographed in India 2001-2019 - Taoist festival in Phuket, Thailand - Kumari (Worshipping of Living Goddess) in Nepal - Nat (Spirit Worship) in Myanmar - Hasidic pilgrimages to Poland and Ukraine |

- Sufism in Egypt, Bosnia, Macedonia and Kosovo

- Hinduism in Bali, Indonesia - Tibetan Buddhism in Nepal, Mongolia and India (Ladakh) - Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar, Thailand and Laos - Zen Buddhism in Vietnam - religious communities in Azerbaijan - Orthodox Christian pilgrimage in Grabarka, Poland - monastic life in Romania - Sunni Islam in Egypt and Bangladesh - Purim in Hasidic communities in Jerusalem, Israel - Animism in Sulawesi, Indonesia - Theyyam cult in Kerala, India - Vodun and traditional religions in Benin |